In 1787, Ephraim Brasher, a goldsmith and silversmith, submitted a petition to the State of New York to mint copper coins. The petition was denied when New York decided not to get into the business of minting copper coinage. Brasher was already quite highly regarded for his skills, and his hallmark (which he not only stamped on his own coins but also on other coinage sent to him for assay [proofing]) was highly significant in early America. Brasher struck various coppers, in addition to a small quantity of gold coins, over the next few years.

One of the surviving gold coins, weighing 26.6 grams and composed of .917 (22-carat) gold, was sold at public auction for $625,000 in March 1981.

We recently purchased a 1783-95 Regulated $2 Gold Ephraim Brasher EB Counterstamp

Struck in the final weeks of December and released in January of the new year, the 1916 Standing Liberty Quarter has one of the lowest mintages of any 20th century coin issued for actual circulation with 52,000 pieces. While they are not of the rarity that the date is often purported to possess, the 1916 is a key date in a popularly collected series and no set of Standing Liberty Quarters may be considered complete without an example.

Hermon MacNeil’s design features the Goddess of Liberty standing within a portal or gateway. Her left arm presents a shield and her gaze is fixed to the east, some would theorize toward a war torn Europe. Her right hand holds an olive branch emblematic of America’s desire for peace. With the influence of the “Art Nouveau” style and her right breast showing, much has been made of the partial nudity exhibited in this obverse. The design was changed part-way thru 1917 with Liberty now clothed in chain mail armor.

Number 43 in Garrett’s 100 Greatest U.S. Coins.

Featured below is a CAC approved AU58.

The Half-Union (also known as Judd-1546 and Judd-1548) is a United States coin minted as a pattern, with a face value of fifty U.S. Dollars. It is often thought of as one of the most significant and well-known patterns in the history of the U.S. Mint. The basic design slightly modified the similar $20 "Liberty Head" Double Eagle, which was designed by James B. Longacre and minted from 1849-1907. It is also #19 on the 100 US Greatest Coins Fourth Edition. The two gold pieces are unique and reside in the Smithsonian Institution.

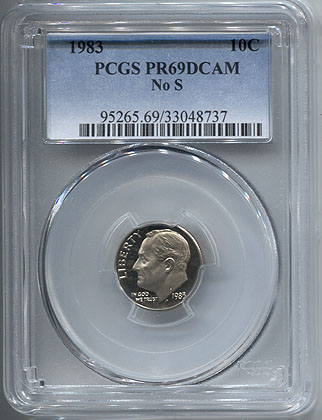

For several different years, some proof Roosevelt Dimes from the San Francisco Mint were struck without the “S” mintmark. For each occurrence, the “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dimes are rare. In a few situations, the coins are significant rarities with only a handful known to exist.

The 1968 “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dime was the first situation. Responsibility for making proof dies rested with the Philadelphia Mint and production took place at the San Francisco Mint. At least one die was sent from Philadelphia lacking the “S” mint mark. A small number of dimes were struck with the die and released before the mistake was discovered. Approximately 12-14 examples are known in all grades. One of these, graded by PCGS as PR68 Cameo, sold for an astonishing $48,865 in September 2006.

Two years later in 1970, more proof Roosevelt Dimes were struck without a mint mark. This time production from an entire die pair was released before discovery, resulting in an approximate mintage of 2,200 of the 1970 “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dimes.

The 1975 “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dime emerged as the rarest of this error type. An extremely small number of proof coins missing the mint mark were released. The coins were so rare that they were not discovered until 1978 when two examples surfaced. These coins are now considered one of the major rarities of the 20th century with an estimated 2 to 5 pieces known. No examples have been graded by either PCGS or NGC.

One more time in 1983, proof dimes were minted without the “S” mint mark and released in some proof sets. The mintage is estimated at the life of a proof die, which at the time was 3,000 to 3,500 coins.

Psssst…we've got one if you’re interested…

The following was written by Chris.

We attended the Whitman Coin Expo in Baltimore last week. This show is held three times a year and is the largest coin show on the East Coast. While the summer show is usually smaller and quieter, the spring and fall shows are typically quite active.

Our business in Baltimore began on Wednesday before the show. We, along with a handful of other dealers, always rent a hotel conference room to do some pre-show trading. Usually these days are busy non-stop from open to close. Unfortunately it was a bit slower than usual this time. Our trading room was somewhat hidden on the second floor of the Hilton. Many dealers we usually see on pre-show days simply didn’t find us. We’ll definitely get a better location next time.

The actual show opened at 8 am on Thursday. The typical mad rush ensued with people hustling to other folks’ tables in an attempt to get an early shot to look at inventory. The first couple of days at just about any coin show are busy from when the bourse floor opens to when it closes. The Whitman Expo was no different.

From a buying perspective, the show was a good one for me. I bought a little bit more than I normally do at this show and came home with about three double-row boxes of newps. I haven’t had an opportunity yet to see what new purchases Tom made, but he no doubt came home with at least two boxes of new purchases himself, and probably more.

Sales were perhaps a tad sluggish for us, but that’s primarily because we weren’t able to show all of our “regular” wholesale dealers that we normally like to see at these shows. They were in attendance but just too busy to look through all of our boxes. Two big coins were sold, however, which certainly helped boost our overall sales. Our Continental Dollar PCGS AU58 CAC and our $50 Pan-Pac Round both sold.

At least with the dealers I dealt with, there was somewhat of a positive vibe. Some encouraging words were said about the market which is something we typically haven’t heard for quite a while. We saw no further softening of prices in the types of coins we typically buy for inventory. It will be interesting to see how the Central States show later this month plays out.

Okay, the business side of this commentary is over. If you aren't already bored to tears, feel free to read on for some personal commentary...

Things I liked about the trip:

*The Light City Festival. This was going on the week of the show. It is apparently the first large-scale, international light festival in the United States. Much of the Inner Harbor area was covered in really neat light displays. Read more at http://lightcity.org. It was a cool thing to see.

*A Così restaurant opened directly across the street from the convention center. Very convenient for those wanting something other than the typical convention center fare. I enjoyed lunch there both Thursday and Friday and it’s sure to become my regular grab-and-go lunch spot for future shows in Baltimore.

*I found a new hangout for socializing in the evenings. I met up with a bunch of coin folks at Supano’s Steak House on Water Street on Thursday evening. The restaurant has a basement replete with several couches and lounge chairs, a small bar, a couple of dart boards, and most importantly a pool table. I held the table for close to two hours until getting my butt kicked by some local kid. With my tail between my legs, I left for the upstairs section to listen for a while to some coin dealers sing karaoke. I did not participate.

Things I didn’t like about the trip:

*The Light City Festival. One thing I usually enjoy during my trips to Baltimore is an evening at the movie theater. I simply do not have the time when I’m home to partake in a film. On Wednesday evening I set out for the movie theater which is usually a 10-12 minute walk from my hotel. Well, I was not expecting the mob of people who were attending the Light City Festival. The pedestrian bridges over the piers were clogged with people going to the different exhibits. It almost seemed like Bourbon Street during Mardi Gras. Nearly 25 minutes later I make it to the theater. For the first time ever I was late to a movie. I totally missed the previews!

*My flight home was horrible. The flight was delayed and I was sitting on the plane for 45 minutes before the captain bothered to come on and explain the reason for the delay (weather). We sat on the tarmac for another hour before we were finally able to take off. Once in the air, it was a roller coaster ride most of the way to Boston. I have no idea how the flight attendants stayed on their feet while serving drinks. It was so rough they announced that no hot beverages would be served for fear of passengers getting hot coffee spilled on them. But we finally landed safely and I was home about 2 ½ hours later than planned. Better late than never when it comes to flying.

Edited to add a few pictures Tom took while attending the Light City Festival: