From all of us here at Northeast, we wish you and yours a very Happy Thanksgiving!

The Lutes and Wing Set:

1943 Coppers that Popularized Numismatics

A miracle was forged from America’s darkest years of conflict. During World War II, the United States Mint altered Lincoln cent production to suit the needs of a desperate nation, but transition was not seamless. The result was a spectacular numismatic legend. The 1943 cent should only have been struck from steel, yet a rare few were accidently made using copper planchets. Pocket-change discoveries of the error would hit like bolts of lightning across the country as millions lusted for the pride, money, and fame they would bring. But just twenty-six examples of this enigmatic off-metal issue ever materialized. Two are here today, united together in a unique, special-purpose NGC holder.

Ignited by the attack on Pearl Harbor, our country was whipped into a frenzy of patriotic fervor. In 1942, alternatives to the copper cent were explored to save materials necessary for war. Cent production waned in the latter months of that year, as copper was diverted from the Mint to munitions factories for use in jacketed bullets and brass shell casings. The coining presses remained silent until February 12th, 1943 (Lincoln’s birthday), when Mint Director Nellie Tayloe Ross ordered production of steel cents at the Philadelphia Mint. Along with the scrap drives, strict rationing, frequent blackouts, and war bonds came a new type of coin.

Conflict ended in 1945, and American GIs returned home to enjoy the postwar boom. Amidst the excitement, one Massachusetts high schooler’s chance discovery left the nation shocked. Seventeen-year-old Don Lutes Jr. of Pittsfield had found a 1943-dated copper cent in his cafeteria change. The Treasury Department denied his discovery, writing that “copper pennies were not struck in 1943,” but renowned numismatist Walter Breen would confirm the authenticity of Lutes’ coin. Lutes had struck the jackpot with his unique error. He received hefty offers for the 1943 copper—including an enticing $10,000—but refused to sell. Lutes finally parted ways with his discovery last year, and Northeast Numismatics acquired the coin.

The public was enthralled by Lutes’ story. People across the country from all walks of life began to feverishly search for their own ‘golden ticket’ 1943 copper. Rumors circulated that Henry Ford would trade a brand-new sedan for one of the errors. Ambitious marketers exploited the situation by selling copper-plated 1943 steel cents as novelties, creating a plague of false flag discoveries that continues today. Each discovery of a genuine example was highly publicized by the media. All the enthusiasm helped contribute to numismatics’ golden age of the 1950s and 1960s, when the ‘hobby of kings’ became as much a part of American life as baseball and barbecues.

Don Lutes was not the first collector to find a 1943 copper cent. Fourteen-year-old Kenneth S. Wing Jr. of Long Beach, California identified a 1943-S (San Francisco Mint) example in circulation during 1944. Wing did not publicize his find, and its existence remained essentially unknown to the numismatic community for many years. Wing was told privately in a 1948 meeting with the Superintendent of the San Francisco Mint that his find was likely genuine, yet the Treasury refused to recognize its authenticity. Smithsonian Curator Vladimir Clain-Stefanelli wrote in 1957 that “The authenticity of this piece is in my opinion beyond doubt.” In 2008, Wing’s family sold the coin to an Orange County dealer, and Northeast Numismatics recently purchased it at auction.

Our NGC two-coin set, containing both the Lutes and Wing specimens, is immensely significant. There are only nineteen known 1943 coppers from Philadelphia and six from San Francisco. Obtaining specimens from both mints is a daunting challenge for even the most deep-pocketed of collectors. A single 1943 Denver copper is known to exist. It became the most valuable Lincoln cent ever after selling in 2010 for a record $1.7 million and will likely not be available again for a very long time. In addition, both the Lutes and Wing specimens are discovery coins -- the first of their kind to publicly surface (a highly desirable fact for collectors). Both coins are exceptionally well-preserved, showcasing minor handling that is consistent with the grade along with rich, glossy chocolate-brown surfaces.

At the heart of the lore that propelled the 1943 copper cent to its celebrity status, these two coins popularized numismatics. They transcend our hobby and would serve as the keystone of any first-rate collection.

Written by Benjamin Simpson

Hard at work...

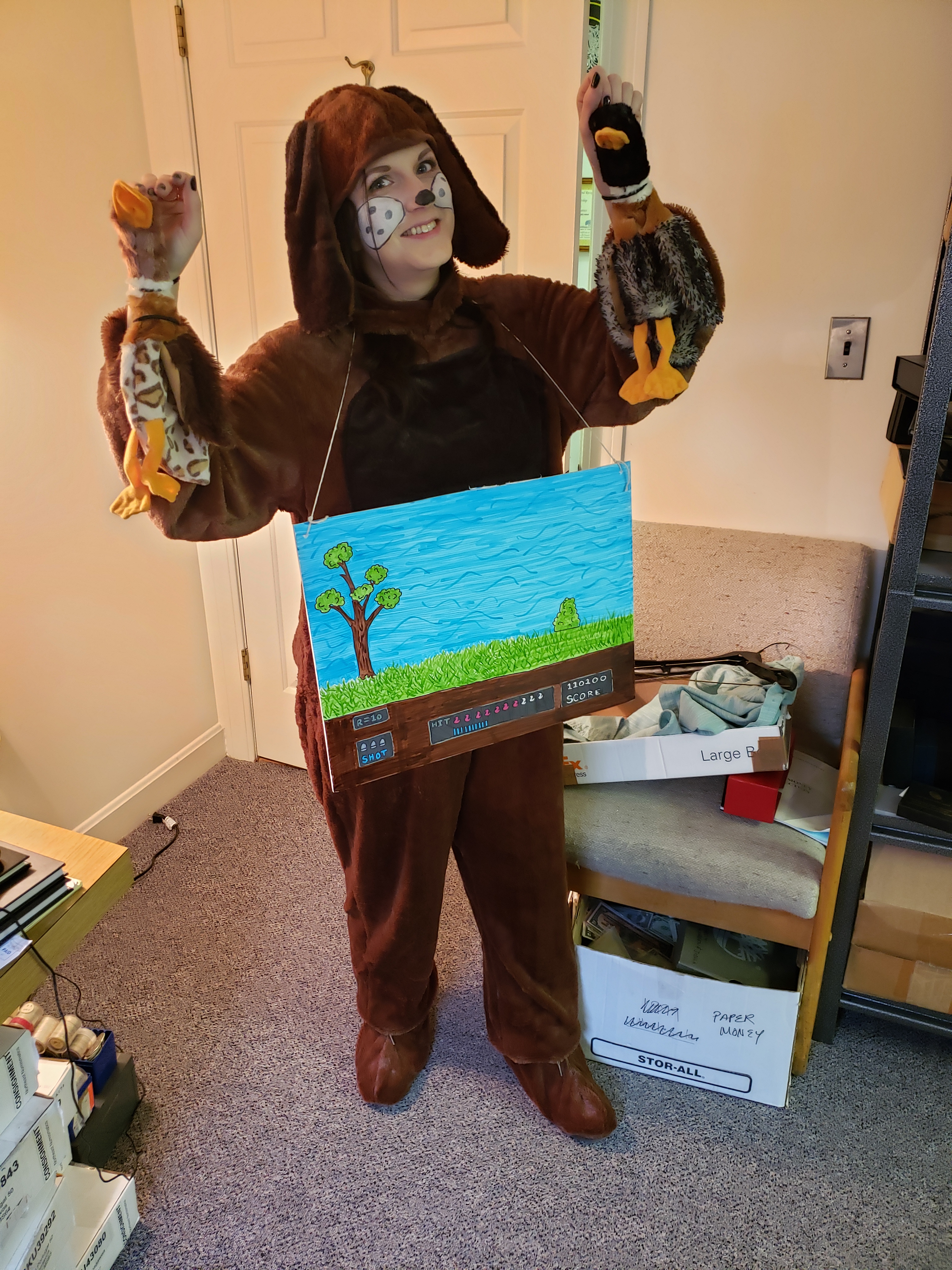

Chris would like to give a special Halloween shout-out to his friend Dave in CA.

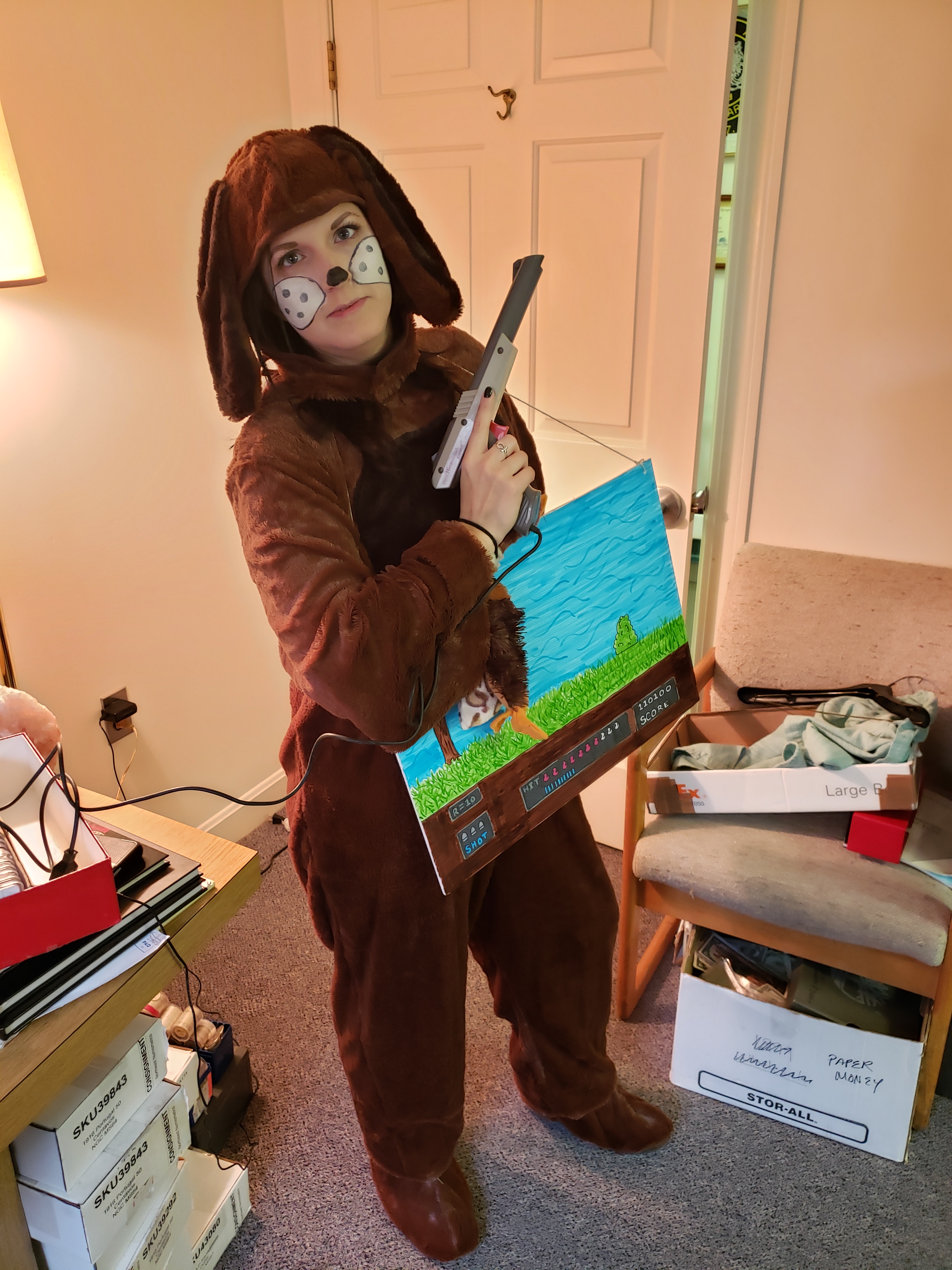

Nintendo anyone?

WOW! The Northeast TEAM is the Best...they are a real 'hoooowl'...

And..."may you have a fang-tastic evening, ghoul-friends! :)

LOL! Thank you, Pat! You too.

This video was shot at the ANA World's Fair of Money in August of this year.

The following was written by Brian:

Yes, I'm asking that question in my very best Jerry Seinfeld voice. Hairlines on coins can be a somewhat confusing topic.

Here's how a typical conversation can go with my boss:

Me: Do you think this would grade proof 63?

Tom: No, too many hairlines. Looks like it would grade proof 62.

Me: Okay, how about this coin? What do you think it would grade?

Tom: I think it would 'no grade'. It would likely go into a Details holder. Too many hairlines.

Ummm, excuse me?

Are we saying some hairlines are better than others? Are not all hairlines created equal? What's The Deal With Hairlines Anyway?

Hairlines are basically tiny, usually shallow, incuse scratches on the surface of the coin from handling, a small amount of circulation or cleaning.

Let's be clear - hairlines are never inherently a good thing, but they *are* acceptable in some cases and not in others. It all boils down to how the hairlines were created. One way is via cleaning a coin (this is the less than acceptable manner, btw). We all know cleaning coins is bad, right? Ok, good, just making sure we're on the same page. Cleaning, as we know, diminishes the luster of a coin. Dimished luster decreases the eye appeal of the coin. Decreased eye appeal lowers the value of the coin (although you can definitely score a better date coin for less $ if you don't mind the cleaning). Here's an example of a harshly cleaned coin that exhibits plenty of hairline scratches and thus would not be considered worthy of grading:

With proof coins, the extent of hairlines is one of the main determinants in grading. You probably won't find much in the way of hairlines on high grade proofs, but you might see a good amount on lower grade examples. Here is a coin graded Proof 61. As you can see, a good amount of hairlines are present, but that is a result of basic handling, album slidemarks, etc.

Please keep in mind that because of the immensely varying degrees, the assesment of hairlines and grade assignments are best left to the experts at the third party grading companies. Please also keep in mind that none of this has to do with die polish, which (and you can thank me later) we'll get into next time. Thanks for reading.